To Issue 169

Citation: Batley J, Barron L, “Gene Therapy in Ophthalmology: Advances and Challenges”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 169 (Mar 2025), pp 24–28.

Joe Batley and Lorna Barron provide an overview of the latest cutting-edge ophthalmic delivery methods and discuss possible future developments.

“THROUGH A TARGETED APPROACH OF MODIFYING EXISTING OR INTRODUCING NEW GENETIC MATERIAL INTO A PATIENT’S CELLS, GENE THERAPIES AIM TO CORRECT THE UNDERLYING CAUSES OF THE DISEASE, RATHER THAN MERELY MANAGING SYMPTOMS – SOMETIMES WITH JUST A SINGLE INJECTION.”

Gene therapy has emerged as a promising frontier in modern medicine, offering potential cures for previously untreatable genetic disorders. These therapies target the rarest of diseases, collectively afflicting millions of people worldwide, where a genetic defect modifies or prevents the proper functioning of cells, often leading to life-threatening conditions. Through a targeted approach of modifying existing or introducing new genetic material into a patient’s cells, gene therapies aim to correct the underlying causes of the disease, rather than merely managing symptoms – sometimes with just a single injection.

Cell, gene and RNA therapies are gaining significant momentum as a novel branch of medicine. Following the first approval of Vitravene (fomivirsen, Novartis) in 1998,1 more than 20 therapies were approved in the following 20 years, compared with more than 30 therapies in the last five years.2,3 One target is ophthalmology, where genetic conditions such as inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), which are thought to affect 5.5 million people worldwide,4 have long posed significant therapeutic challenges. The success of therapies such as Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl, Spark Therapeutics, PA, US) – the first US FDA-approved gene therapy for an eye-related condition – has spurred rapid advancements in the field.

GENE THERAPIES

Gene therapies cover a broad class of treatments with the same underlying goal – manipulating the DNA of a patient’s cells to treat a disease at its root cause. In general, these diseases cannot be treated or managed through conventional drugs and, in the case of inherited retinal diseases, often lead to blindness.

As a class of treatments that specifically targets a genetic defect and the individual cells that are affected, the variation in different genetic diseases leads to a varied approach for transfecting the new genetic material. Broadly, these can be categorised into two methods with different requirements for the delivery device used:

- In Vivo: The genetic material is delivered directly into the patient’s body, typically enclosed in a carrier, and interacts with the target cells.

- Ex Vivo: Cells are modified outside the body before being delivered to the patient. These may be from the patient or a donor.

With many different approaches under development, competition is intense. This article will focus on the in vivo approach.

“THE OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPY PIPELINE IS EXPANDING, WITH MULTIPLE CANDIDATES EXPLORING SEVERAL KEY APPROACHES TO DELIVERY.”

EMERGING THERAPIES AND CLINICAL PIPELINE

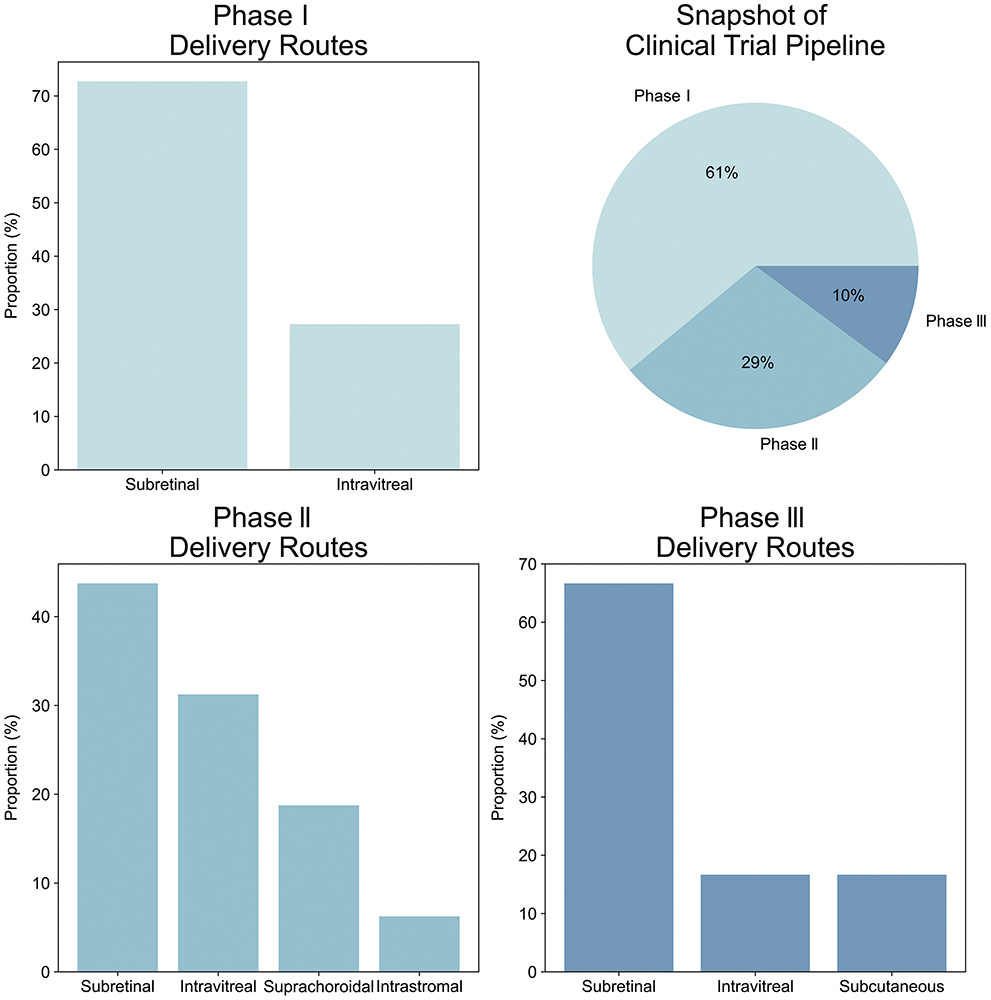

The ophthalmic gene therapy pipeline is expanding, with multiple candidates exploring several key approaches to delivery (Figure 1). Therapies often use adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) as a delivery vector to introduce a corrected copy of a single gene but monoclonal antibodies, genetic modifiers or even novel optogenetic approaches are also used.

A key AAV-based therapy is Luxturna to treat RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy (RD). The ongoing PERCEIVE study has reported results up to two years demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of the treatment in real-world settings.5 After this first success for RD patients, AAV-based gene therapy is now being applied to other diseases. Notably, MeiraGTx (NY, US), through subretinal injection, has demonstrated significant vision improvement in treated children, all of whom were legally blind before therapy.6

AbbVie and REGENXBIO (MD, US) are taking gene therapy to new heights with their Phase III trial, ASCENT, for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD). The treatment comprises a one-time subretinal injection of an AAV-based vector to deliver a gene encoding for a monoclonal antibody fragment to inhibit the formation of abnormal blood vessels.7 They are also exploring a suprachoroidal approach, enabling in-office delivery of the therapy in their Phase II trial, AAVIATE, which has reported positive interim results.8

Occugen’s (PA, US) OCU400 takes a different approach. As an AAV-based gene-agnostic modifier therapy, it delivers the protein encoding gene NR2E3, regulating multiple gene networks to restore retinal homeostasis.9 The liMeliGhT Phase III trial reports that 89% of patients experienced vision preservation or improvement, and this approach may be beneficial for multifactorial diseases such as AMD.

While AAV-based therapies require viable cells for transfection, optogenetic therapies offer an alternative that seeks to restore vision independent of the underlying genetic defect by introducing light-sensitive proteins into surviving retinal cells, enabling them to function as photoreceptors. GenSight Biologics’ (Paris, France) GS030 introduces a light-sensitive protein into retinal ganglion cells and stimulates them with intense light. PIONEER Phase I/II results show patients transitioning from low light perception to object recognition after one year.10 As optogenetics does not require viable photoreceptors, it is a promising option for late-stage retinal diseases.

CHALLENGES IN OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPY

IRDs, genetic mutations affecting the photoreceptors or retinal pigment epithelium, are a key target for ophthalmic gene therapies. Over the years, researchers have identified many key genes associated with IRDs but, since these diseases are rare, developing this knowledge is difficult and time-consuming.

Despite significant advancements in the field, and the success of drugs such as Luxturna, there are still fewer approved therapies for ophthalmology than other therapeutic areas.3 There are many general challenges to gene therapies – developing customised therapies for rare mutations remains costly, time-intensive and with impacts on manufacturing scalability. However, some challenges specific to ophthalmic therapies include:

- Disease Progression: Therapy is most effective when sufficient retinal cells remain. Late-stage diseases may require stem cell transplantation or retinal implants.

- Safety Concerns: Viral vectors can trigger inflammation, while invasive techniques risk retinal detachment and infection.

- Targeted Delivery: The blood-ocular barrier limits the effectiveness of systemic therapies, requiring local delivery.

DELIVERY METHODS FOR OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPY

Targeted delivery of gene therapies to the eye can be a significant challenge. The eye is a highly sensitive and complex organ, composed of various layers, internal membranes and barriers that can impede drug efficacy. The blood-retina barrier restricts transport to water, ions, and proteins, limiting the effectiveness of systemic infusion therapies. Additionally, internal barriers, such as the internal limiting membrane, hinder the movement of therapeutic agents between the vitreous humour and retinal cells.

“GENE THERAPY REQUIRES DIRECT ACCESS TO TARGET CELLS FOR EFFICIENT GENETIC MATERIAL TRANSFER AND, AS MANY OCULAR DISEASES AFFECT THE MACULA AND RETINA AT THE BACK OF THE EYE, THIS NECESSITATES LOCALISED DELIVERY METHODS RATHER THAN SYSTEMIC INFUSION.”

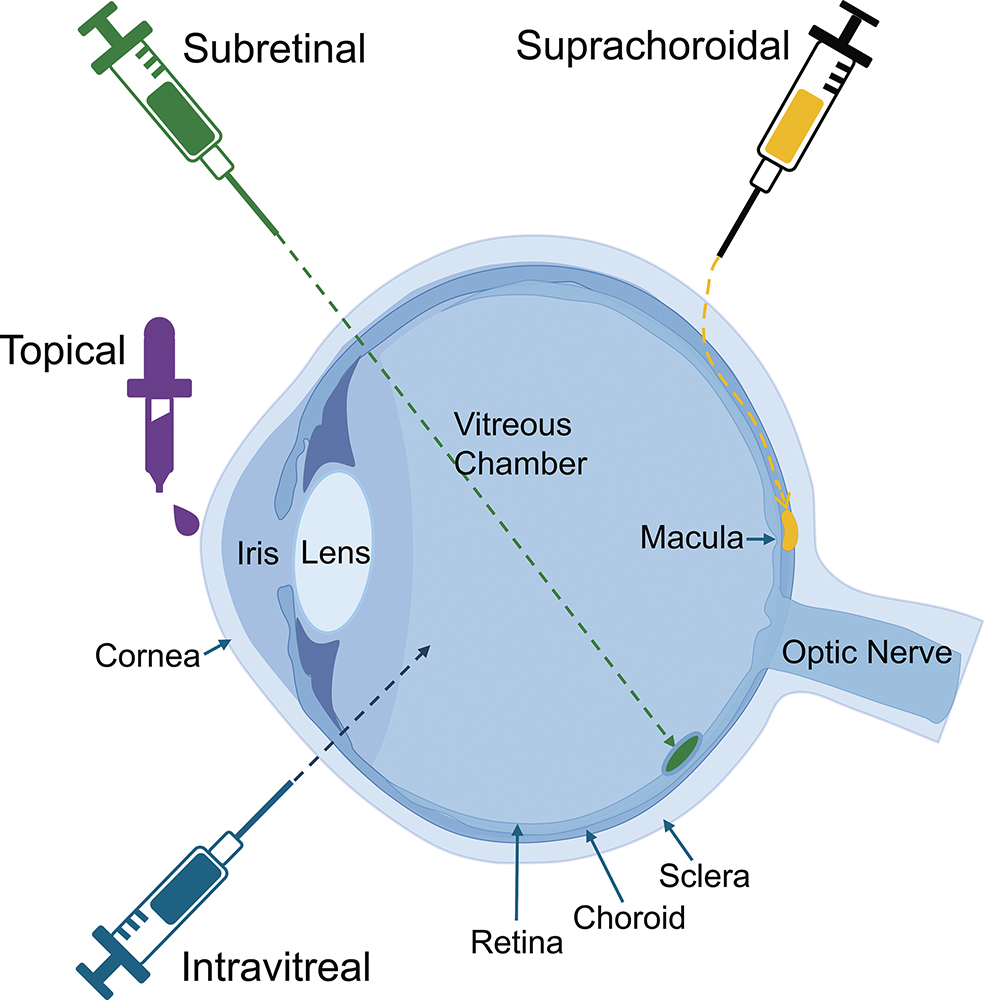

Gene therapy requires direct access to target cells for efficient genetic material transfer and, as many ocular diseases affect the macula and retina at the back of the eye, this necessitates localised delivery methods rather than systemic infusion. Since topical drug delivery lacks the bioavailability needed for effective gene therapy,11 more invasive techniques are required. As the field evolves, emerging technologies aim to enhance precision, minimise invasiveness and improve therapeutic outcomes.

Several delivery methods are being explored to ensure effective and targeted gene transfer (Figure 2). Historically, the first gene therapies, such as Luxturna, have used extremely delicate surgical approaches to delivering genetic materials to the eye. However, as is a common trend in drug delivery, more recent years have seen a focus on methods that can be delivered in a clinic or office setting, aimed at reducing costs and risks. Each approach is presented here to help understand the challenges involved.

Surgical based

A widely used delivery method (Figure 1), most notably for Luxturna, subretinal injection involves creating a localised retinal detachment or “bleb” to facilitate direct gene transfer to the photoreceptors. This technique ensures precise targeting of affected cells but requires a complex surgical procedure known as pars plana vitrectomy, in which the vitreous of the eye is removed to gain access to the back of the eye. While subretinal injection has demonstrated long-term efficacy, its invasiveness necessitates highly specialised surgical expertise.

To produce a bleb retinal detachment, the surgeon will push the cannula through the retina before injecting fluid. Complications can occur, including neurosensory retinal trauma and damage to delicate subretinal structures.12 Surgeons often control the delivery of the therapy by using foot-pedal control of pneumatic pressure to drive the syringe plunger. However, this technique lacks direct control of flow rate and volume, which may lead to unintended bleb propagation or damage to retinal cells.

As the sub-retinal approach is the most common delivery method seen across therapeutic pipelines (Figure 1), many alternative devices are in development. One such device is Altaviz’s Advent, which aims to control flow rates and dose while providing a low force actuation. However, shifting to simpler, in-office approaches may offer improved accessibility and lower costs.

Figure 1: Snapshot of clinical trial pipeline. Subretinal injections are currently the primary delivery mode across all clinical phases, with intravitreal secondary.

Recent years have seen a growth of a new method using the suprachoroidal space.

Clinic based

In-office treatment at local clinics eliminates the need for large surgical suites and specialised equipment. Intravitreal injection (IVI), a common ophthalmic delivery method routinely employed for a range of conditions, has shown promise for gene therapy, thanks to its relative simplicity and cost effectiveness. Compared with subretinal injections, IVIs are less invasive and do not necessitate extensive surgical equipment. Injection guides, such as Precivia (FCI, MA, US) and SP.eye™ (Andersen Caledonia, Strathclyde, UK), help standardise depth and positioning, improving precision.

Since gene therapies are typically produced in small quantities and require extreme cold storage, they are commonly shipped in vials. Standard injection syringes are a well-established method for transferring and administering these doses but their accuracy can be a limitation – especially for the typical 50 μL doses. To address this, companies such as Credence MedSystems and Congruence Medical Solutions are developing devices that improve dosing precision. However, prefilled syringe solutions, such as those from Credence, may not be suitable for gene therapies due to the need for ultra-cold storage.

Despite its advantages, IVI presents some challenges. Potential complications include floaters, intraocular pressure fluctuations, inflammation and infection. While IVI remains the preferred in-office method (Figure 2), its limitations have driven interest in alternative approaches, particularly suprachoroidal injection.

Figure 2: Key parts of the eye and the modes of delivery for ophthalmic therapies.

The suprachoroidal space lies beneath the sclera and encircles the posterior eye. Unlike IVIs, this approach does not penetrate the vitreous, reducing the risks of vitreous haemorrhage and intraocular pressure fluctuations. Additionally, the natural fluid dynamics of the suprachoroidal space help distribute the delivered therapy more evenly across the retina. Clearside Biomedical (GA, US) has pioneered the development of suprachoroidal injection devices, introducing a custom microneedle injector currently being tested in multiple gene therapy trials.

Although promising, suprachoroidal injection presents challenges. Determining the exact thickness of the sclera can be difficult, making depth control a key concern. The Clearside device has both 900 μm and 1,100 μm microneedles, with studies showing the former is suitable for 78% of injections13 and so, in some cases, a second attempt is required. As a result, other companies, such as Oxular (recently acquired by Regeneron, NY, US), are developing microcatheter-based techniques, while early-stage research explores adjustable microneedle devices. Additionally, the procedure takes longer than IVI, which can cause discomfort. However, with increasing clinical adoption and a growing research pipeline, suprachoroidal injection is one to keep an eye on.

Finally, a major challenge in gene therapy is the immune response triggered by viral vectors. To address this, researchers are investigating non-viral approaches such as electroporation and optogenetics. Electroporation uses electric fields to enhance the uptake of genetic material, while optogenetics employs light pulses to activate gene expression. Both methods still require local injection for delivery, but they offer the potential for safer, more flexible gene transfer. While these technologies require further optimisation, they represent a promising evolution in ophthalmic gene therapy.

“WITH ONGOING CLINICAL TRIALS AND INCREASING REGULATORY APPROVALS, GENE THERAPY HOLDS THE POTENTIAL TO REVOLUTIONISE THE TREATMENT LANDSCAPE FOR INHERITED AND ACQUIRED OCULAR DISEASES.”

THE FUTURE OF OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPY

The field of ophthalmic gene therapy continues to evolve, driven by advances in vector design, delivery technologies and gene-editing tools. As research progresses, the development of mutation-independent therapies, improved non-viral delivery systems and personalised medicine approaches will likely enhance treatment efficacy and accessibility.

With ongoing clinical trials and increasing regulatory approvals, gene therapy holds the potential to revolutionise the treatment landscape for inherited and acquired ocular diseases. However, the costs to develop and manufacture these therapies can be extremely high, making effective delivery of the dose to a complex organ, such as the eye, a critical requirement. Meeting optimal clinical efficacy and safety will require dual development of the therapies and delivery methods, avoiding generic methods for a bespoke treatment. However, by addressing these challenges and refining delivery techniques, researchers and clinicians can pave the way for a future where vision loss due to genetic disorders becomes a thing of the past.

REFERENCES

- Shahryari A et al, “Development and Clinical Translation of Approved Gene Therapy Products for Genetic Disorders”. Front Genet, 2019, Vol 10(868), pp 1–25.

- Ginn SL et al, “Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2023 – an update”. J Gene Med, 2024, Vol 26(8), pp 1–15.

- “Gene, Cell, & RNA Therapy Landscape Report – Q4 2024 Quarterly Data Report”. J Am Soc Gene Cell Therapy, 2024.

- Ben-Yosef T, “Inherited Retinal Diseases”. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, Vol 23(21), art 13467.

- Fischer MD et al on behalf of the PERCEIVE Study Group, “Real-World Safety and Effectiveness of Voretigene Neparvovec: Results up to 2 Years from the Prospective, Registry-Based PERCEIVE Study”. Biomolecules, 2024, Vol 14(1), art 122.

- Sai H et al, “Effective AAV-mediated gene replacement therapy in retinal organoids modeling AIPL1-associated LCA4”. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids, 2024, Vol 35(1), art 102148.

- “ABBV-RGX-314 for Retinal Diseases”. Web Page, REGENXBIO, 2023.

- “REGENXBIO Announces Dosing of First Patient in Phase II AAVIATE™ Trial of RGX-314 for the Treatment of Wet AMD Using Suprachoroidal Delivery”. Press Release, REGENXBIO, Sep 2020.

- Lam BL et al, “OCU400 Nuclear Hormone Receptor-Based Gene Modifier Therapy: Safety and Efficacy from Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial for Retinitis Pigmentosa Associated with NR2E3 and RHO Mutations”. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2024, Vol 65, art 406.

- S ahel JA et al. “Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy”. Nat Med, 2021, Vol 27(7), pp 1223–1229.

- Subrizi A et al, “Design principles of ocular drug delivery systems: importance of drug payload, release rate, and material properties”. Drug Discov Today, 2019, Vol 24(8), pp 1446–1457.

- L’Abbatea D et al, “Biomechanical considerations for optimising subretinal injections”. Surv Ophthalmol, Vol 69(5), pp 722–732.

- Wan CR et al, “Clinical characterization of suprachoroidal injection procedure utilizing a microinjector across three retinal disorders”. TVST, 2020, Vol 9(11), art 27.