To Issue 182

Citation: Schreiber S, Wember T, Block S, “Safety by Design for Drug Delivery Devices”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 182 (Jan 2026), pp 72–75.

Visit Scherdel at Pharmapack Paris! – Stand 4G108

Professor Stefan Schreiber, Dr Theo Wember and Sebastian Block discuss how using Design of Experiments methodology can provide insights into the manufacturing process of power springs that can enable manufacturers to more robustly control variables and produce more consistent outputs.

Scherdel Medtec is an expert in metal components for drug delivery devices, manufacturing precision parts for the drive and dosing systems used in autoinjectors, pen injectors and inhalers, where ensuring correct and safe functionality is essential for patient safety. For this reason, Scherdel places a strong emphasis on product quality. Potential influences on functional performance can be evaluated at an early stage using a Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology, including for effects originating from material suppliers. This enables an optimal process setup and a clearly defined set of process parameters that can reliably prevent deviations from product specifications.

“EXPERIENCED DEVELOPMENT ENGINEERS CAN EASILY IDENTIFY 20 OR MORE PARAMETERS THAT INFLUENCE KEY PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS.”

POWER SPRINGS

Developing a power spring is a demanding, multistep process. Experienced development engineers can easily identify 20 or more parameters that influence key performance characteristics. However, not all of these parameters – particularly those derived from material properties – can be controlled during manufacturing. Understanding the interactions between these factors is therefore essential to achieving consistent and optimal product quality. This is where DoE provides significant value.

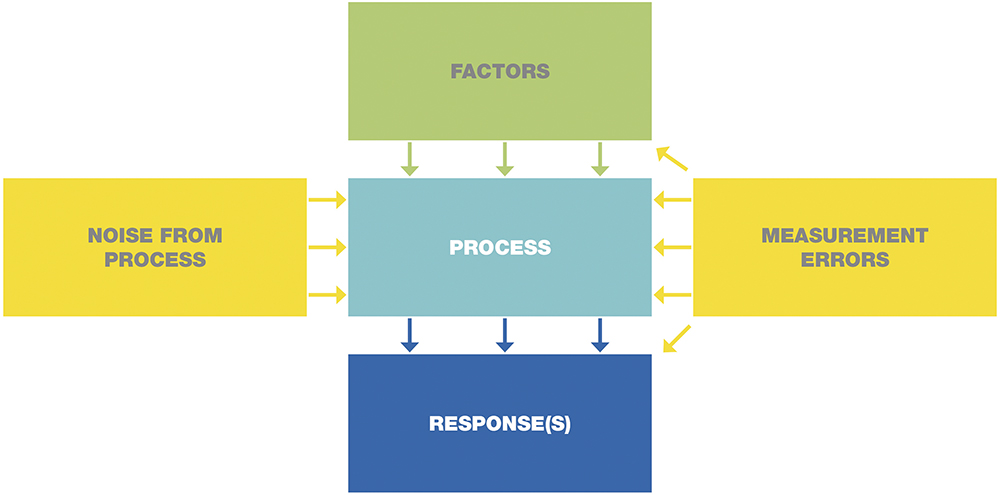

Figure 1 shows the process model used throughout the DoE framework. In this model, the manufacturing process is ideally influenced by controllable factors (green), which lead to the desired responses (blue). Noise effects (yellow) represent stochastic influences originating from upstream processes or the measurement system. DoE provides objective evidence of how production is affected by noise and how robust process windows can be established to maintain consistent performance.

Figure 1: Process model.

Winding Process Manufacturing

Before applying DoE, it is necessary to understand the many aspects of the manufacturing process. Although the fundamental theory behind power springs is widely accessible, the complexity of the manufacturing sequence makes it impractical to create a comprehensive analytical model of the entire process. In particular, friction between loaded and unloaded coils cannot be represented by analytical equations reliably.

Power springs are typically manufactured through a winding process using an austenitic stainless-steel strip of specified width and thickness. Several factors influence the quality, function and reliability of the final product. Key steps of the process include:

- Supplied Materials: For this type of spring, Scherdel typically uses cold-rolled steel strips with predetermined technological parameters, such as tensile strength, chemical composition and geometric properties, all defined in close co-ordination with suppliers.

- Cold-Forming: Various spring designs used in medical devices, such as torsion springs or power springs, are formed using dedicated cold-forming machinery. Relevant factors include machine-specific settings and the condition of tooling (predictive maintenance).

- Heat Treatment: Heat treatment affects cold-setting behaviour and tensile strength. Important parameters include oven temperature, tempering duration and possible positional effects within the oven.

- Assembly: Depending on the specific spring design, an assembly step may be required. Scherdel can provide complete drive systems, including housing, directly to customers.

- Quality Control: Customers typically specify the required force or torque values. Additional dimensional or functional requirements may also apply. Scherdel treats measurements as its own process and works to minimise measurement variation to ensure the highest possible consistency.

The Equations Behind Power Springs

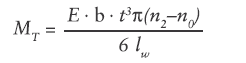

According to the established “spring manual” (available upon request from Scherdel Medtec), the torque MT of a power spring without coil clearance is defined as:

- E: Young’s modulus of the material

- b, t: Width and thickness of the strip

- n0, n2: Number of coils in the spring’s released and fully loaded status

- lw: Spring length is defined as:

![]()

With n1 as the number of coils in an intermediate loading and R2 to R5 as the radii defined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Geometry of a power spring.

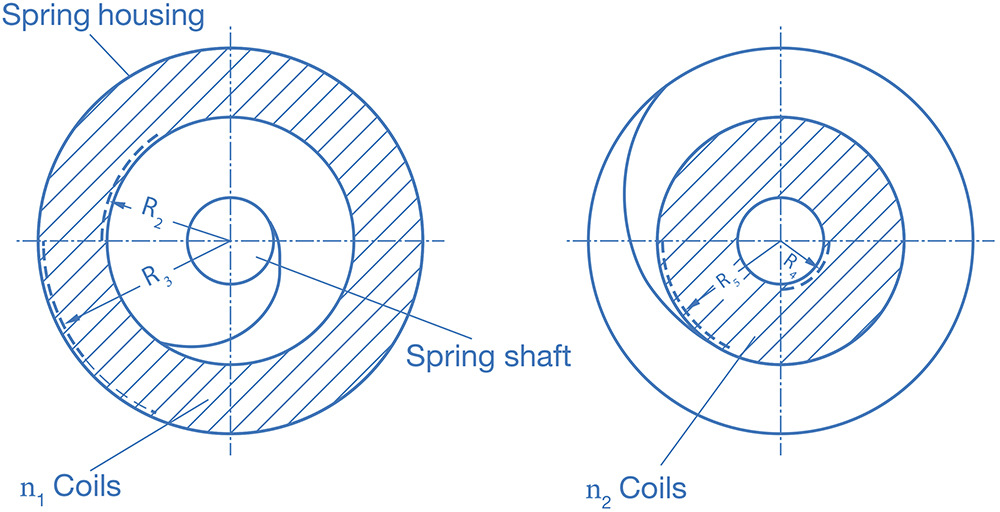

Figure 3 presents a simulated torque-angle curve illustrating an exemplary requirement of 35 Nmm at the beginning and 30 Nmm at the end of use over 10 revolutions (3600°). The torque drops to zero in the 11th revolution, indicating full release. The complexity of this behaviour and the many interactions within the production process demonstrate the necessity of a structured DoE approach.

Figure 3: Exemplary simulated torque versus angle diagram of a power spring used in the DoE analyses.

DESIGN OF EXPERIMENTS

From more than 20 possible identified factors, six were selected for the study. Three factors and their respective ranges are disclosed, while the further three (x4 to x6) remain confidential (Table 1). The investigation focused on the winding process. The responses reflect the initial torque, end torque and one additional undisclosed parameter (Table 2). The DoE methodology is a tried and tested sequence of preparatory works and in-depth mathematical analyses beyond the scope of this text, so only a rough sketch is covered here.

| Factors | Symbol | Min | Min | Units |

| Coil Thickness | Thickness | 95 | 105 | μm |

| Tempering Temperature | Tempering Temp | 340 | 420 | °C |

| Tempering Time | Tempering Time | 30 | 40 | min |

| -undisclosed- | x4 | |||

| -undisclosed- | x5 | |||

| -undisclosed- | x6 |

Table 1: List of factors.

Using engineering reasoning and the theoretical background of power spring behaviour, a polynomial model was created linking all six factors to the three responses. The model contained 26 coefficients, representing the minimum number of required experiments. The full “design space” of the six factors would require 324 experiments. Using a D-optimal design, a practical subset of 32 experiments was selected.

| Responses | Symbol | Goal | Low | High | Target | Units |

| Initial Torque | Torque Ini | Target | 30 | 40 | 35 | Nmm |

| End Torque | Torque End | Target | 25 | 35 | 30 | Nmm |

| -undisclosed- | Maximise |

Table 2: List of responses.

“THIS IS A KEY PRINCIPLE OF TAGUCHI’S ROBUST DESIGN STRATEGY – USE CONTROLLABLE FACTORS TO MINIMISE THE INFLUENCE OF UNCONTROLLABLE ONES.”

Each experiment was carried out ten times, resulting in a total of 320 observations. While this number is only slightly less than the aforementioned 324 experiments, repeating a single experiment ten times only requires a fraction of the effort of performing 10 different experiments. After the experiments were executed and analysed, the model for the response “Initial Torque” achieved an adjusted R2 = 0.89, indicating that 89% of the observed variation is explained by the model – an excellent result.

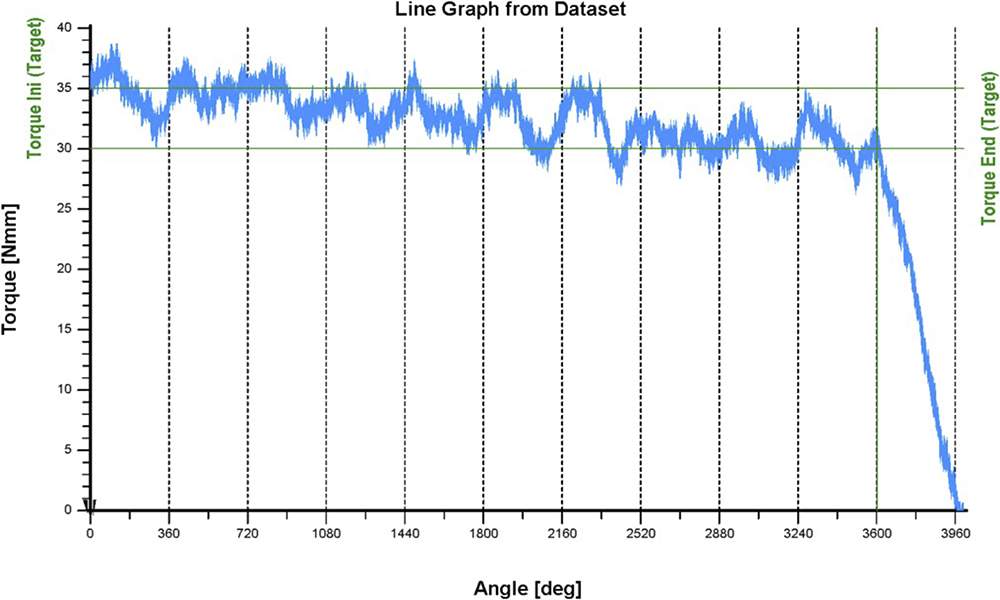

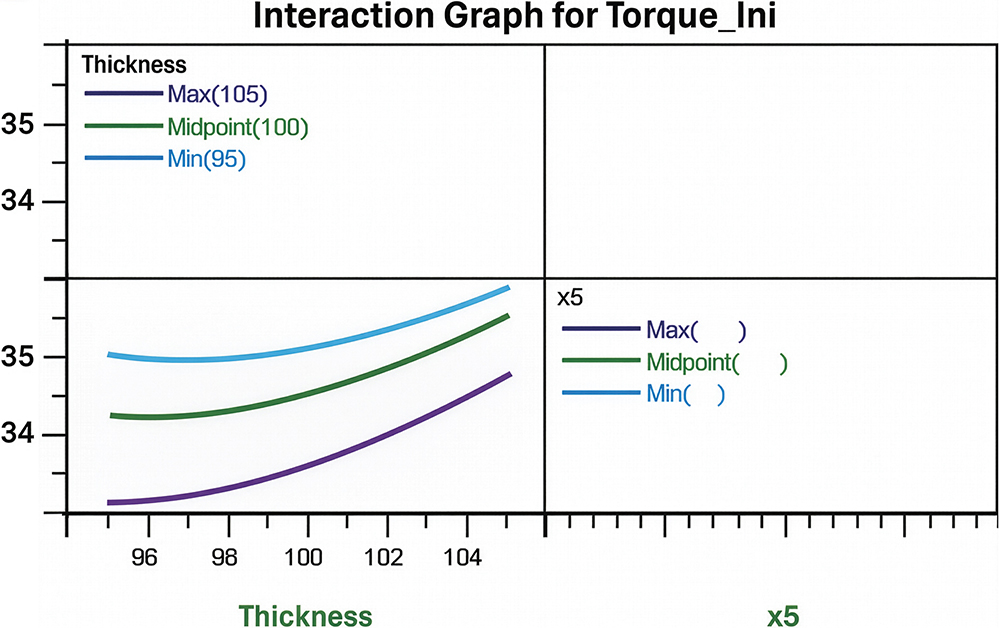

One of the most notable findings was the interaction between coil thickness and factor x5, shown in Figure 4. Although coil thickness was a controlled factor in the experimental setup, it becomes an uncontrolled noise factor during real production because it is defined by the supplier. The interaction plot shows that at the minimum level of x5, the impact of coil thickness variation is significantly reduced and the curve becomes flatter. Thus, the process becomes more robust. This is a key principle of Taguchi’s robust design strategy1 – use controllable factors to minimise the influence of uncontrollable ones.

Figure 4: Interaction Graph for initial torque.

After this investigation, the statistically proven models for all three responses constitute the ultimate toolset for finding good process parameters and identifying appropriate corrective measures in case of process deviations.

“FOR SAFETY-CRITICAL COMPONENTS, ESPECIALLY THOSE USED IN DRUG DELIVERY DEVICES, SAFETY MUST BE A MATTER OF DESIGN, NOT A MATTER OF CHANCE.”

A MATTER OF DESIGN

As in many production processes, the large number of controllable and uncontrollable factors presents both opportunities and challenges. To achieve stable production while meeting stringent quality requirements, all contributing factors must be understood and controlled. The authors strongly recommend implementing a rigorous quality-assurance strategy based on DoE. As demonstrated, DoE reveals valuable insights into system performance – insights that would otherwise remain hidden. When beneficial interactions such as the one between coil thickness and factor x5 are identified, the resulting improvements in process robustness can be substantial.

Such findings would rarely be discovered without a systematic approach. For safety-critical components, especially those used in drug delivery devices, safety must be a matter of design, not a matter of chance. DoE offers a powerful methodology to reduce costs and accelerate time-to-market using a minimal number of trials while maximising insights.

REFERENCE

- Taguchi G, “Introduction to Quality Engineering: Designing Quality into Products and Processes”. Asian Productivity Organization, Jun 1986.