Citation: Foster M, “When Secondary Packaging is a Primary Concern.” ONdrugDelivery Online, August 15th, 2023.

Oliver Design‘s Mark Foster discusses the challenges to optimising primary and secondary packaging for parenteral drug delivery devices, including higher level challenges from the patient perspective, as well as how these challenges present opportunities for device developers to stand out in the market.

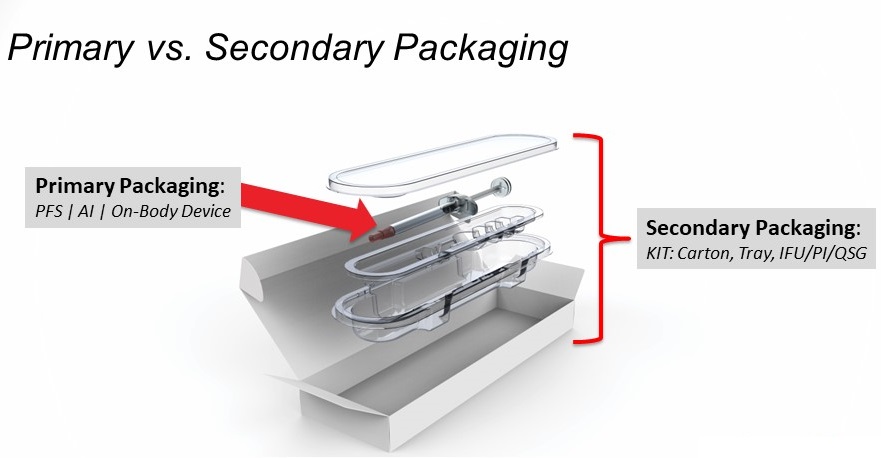

Let’s discuss primary versus secondary packaging in the growing realm of patient and caregiver administered therapies in the injection space. Through the lens of primary packaging for that market, most will be familiar with prefilled syringes, autoinjectors, pen injectors and wearable injectors, all of which are combination devices. It is not an overstatement to say that combination devices are mission critical drug delivery systems – they are the key to proper therapeutic administration. Without combination devices, the therapies they contain could not be administered by the patient or caregiver.

However, it is important to note that secondary packaging for these devices also holds an important role in proper administration. It can be frustrating for packaging professionals to see how little attention has been placed on the importance of secondary packaging for parenteral therapies. Time and time again, it has been shown how important the role secondary packaging plays is for biopharma products. Secondary packaging is where companies can make their product stand out and, more importantly, move more quickly through the packaging development phase (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Primary and secondary packaging of a drug delivery device. (Image courtesy Oliver Design.)

There are several different examples that represent packaging challenges from the patient perspective. These challenges are increasingly important considerations when developing packaging solutions for patient-administered therapies. However, to understand patient challenges, it helps to first review the high-level objectives of both primary and secondary packaging.

PRIMARY PACKAGING OBJECTIVES

There are five key drivers governing the design of primary packaging. It is important to review and understand these drivers before discussing how secondary packaging can answer the challenges that arise from them.

Protection

Primary packaging helps protect the drug from contamination and damage. This is especially important for parenteral drugs, as they are administered directly into the bloodstream and must be pure, safe and effective.

Preservation

Primary packaging plays a key role in preserving the stability and potency of the drug over time. This supports drug efficacy throughout the product’s intended shelf-life.

Safety

Primary packaging helps to prevent accidental exposure of the drug and minimises the risk of injury during the administration process. Examples of safety features include tamper-evident seals, colour-coding, warning symbols and other features to ensure proper handling.

Ease of Use

Especially for patient-administered therapies, primary packaging must be user-friendly and intuitive. Ease of use factors promote administration using aspects such as simple opening methods, easy-to-understand labelling and instructions for use that a patient or caregiver can easily follow.

Compliance

Primary packaging also supports patient compliance with dosing instructions. Clear instructions for use and dosing information are the primary means by which the patient interacts with the medication, thereby helping (or hindering) correct dosage and administration needed to receive effective treatment.

SECONDARY PACKAGING CHALLENGES

In understanding the objectives of primary packaging, several baseline challenges to optimal packaging solutions present themselves. It is these challenges that bring secondary packaging into the limelight as the key to alleviating these concerns. As with industry’s overarching packaging goals, pre-emptively considering secondary packaging challenges can improve even the earliest packaging system concepts.

User Errors

Human factors studies have become a mainstay of packaging design – for good reason. Human factors reveal common user errors associated with parenteral drug therapies, including incorrect dose administration, incorrect injection site selection and the risk of drug contamination. These errors can have serious consequences for patient safety, highlighting the need for user-centric design for parenteral drug products and delivery systems.

Clear Labelling and Instructions

Unclear labelling and instructions are a surprisingly common source of confusion and error in parenteral drug administration. How-to instructions must be easy to read, clear and accessible to all users, including those with limited literacy or visual acuity. Where engineers, scientists and executives fluently converse in technical language, patients and caregivers outside the industry likely have little context or knowledge other than that which they have gained while managing their own (or their loved one’s) medical condition.

User Preferences

Human factors studies have also shown that user preferences play a significant role in the selection and use of parenteral drug delivery devices. Factors such as device size, shape, weight and portability can influence user preferences and impact their willingness to use the device as prescribed.

Need for Training and Support

Lastly, human factors studies have demonstrated the need for comprehensive training and support to ensure that users are able to safely and effectively use their parenteral drug delivery devices. Providing clear written instructions, hands-on training and demonstration in a clinical setting all improve a patient’s ability to correctly self-administer their medication, and the ability for patients to easily access ongoing support should also be considered.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE CHALLENGES

With the common goals and challenges of packaging in the front of the mind, discussion naturally segues into considering the patient-perspective challenges mentioned earlier. These challenges can be thought of as “next level” opportunities that can transform into early success in parenteral drug packaging systems.

Medical Condition or Disease

The first thing to look at is simple – what is the patient being treated for? That answer prompts the next question – how should their condition influence the packaging design? This is well-addressed for many therapies, especially for conditions that impair a patient’s physical ability. However, it becomes more intriguing when developing therapies for patients who suffer from neurological conditions such as high-anxiety, PTSD or even disorders such as bi-polar disorder or schizophrenia. How patients with complex conditions interact with and interpret instructions must be integrated into packaging design wherever possible, often requiring the assistance of behavioural specialists.

Human factors studies solicit participants that might not always be perfectly aligned with the condition but represent the affected population, called “surrogates”. In these studies, the secondary packaging would seek to positively guide the surrogate’s mindset by slowing down the process and encouraging them to read the step-by-step directions.

Administering to Children

Another therapy area that requires attention is paediatrics. Consider a caregiver who needs to administer human growth hormone to a child. Treatment would start with a weekly injection over an 18-month period. Taking the child to the doctor’s office for the weekly injection would be the historically common approach; for a nurse who administers injections all day long, such a task is no big deal. But what about parents who are provided with a kit for injections to be given at home? They need that kit, its instructions and the injection process to be as plain, intuitive and encouraging as unpacking a new iPhone.

To expand the example, consider a scenario where the child’s parents must travel away, and the responsibility of administering the injection falls to a grandparent or other temporary guardian. In this scenario, a new level of urgency emerges for those instructions to be clear and supportive.

Negative Transfer

Finally, consider a participant in a human factors study who picks up the autoinjector and administers it in the incorrect administration site. When asked by the facilitator why they injected it there, the response is that they have been using an injector for years, or have a family member who uses an injector, and that is where they have always administered the injection. This is referred to as “negative transfer,” which is when a patient’s previous experience influences and causes incorrect drug administration. Instructions and labelling need to consider this possibility and combat it wherever possible.

CONCLUSION

Industry attention to differences between in-clinic and at-home administration is sure to bring new opportunities for packaging professionals and manufacturers. By starting at the source – the patient and caregiver – it is possible for the industry to find and deliver a new generation of secondary packaging that serves and supports safe, simple and effective treatment of a growing number of chronic medical conditions and diseases.

Images courtesy Oliver Design.