To Issue 181

Citation: Guillemot L-H, Pagnoud E, “Evolving Elastomer Stopper Technologies for a Changing Regulatory Landscape”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 181 (Dec 2025), pp 16–21.

Dr Laure-Hélène Guillemot and Edouard Pagnoud assess the impact of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances ban on elastomer stoppers and the resulting extractables and leachables challenges, highlighting how Aptar Pharma is developing new solutions to meet both regulatory expectations and customer needs.

In parenteral drug delivery, extractables and leachables (E&L) continue to be one of the most critical considerations for scientists and regulatory authorities alike. As drugs become increasingly complex, the integrity of the packaging system directly influences both product efficacy and patient safety.1

Within this framework, elastomeric stoppers and plungers play a pivotal role in maintaining container closure integrity and drug stability.1 However, as they are the primary interface between the drug product and packaging materials, there is potential for unwanted chemical migration.2

The evolving regulatory landscape, notably the global movement towards restricting per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), is reshaping material strategies and accelerating innovation across the parenteral packaging industry (ECHA, Annex XV, 2023).3,4

IMPACT OF EXTRACTABLES & LEACHABLES

Traditional Migration Dynamics

Chemical migration between the stopper surface and the drug product occurs primarily through direct contact, particularly in liquid and long-term formulations.2,5 Migration can occur bidirectionally:

- Drug-to-Stopper Migration: API or formulation excipients can diffuse into the elastomer matrix, which can lead to chemical degradation of the stopper, changes in physical properties or altered surface characteristics. Such interactions can reduce drug potency or modify release profiles, ultimately compromising therapeutic performance.5,6

- Stopper-to-Drug Migration: Additives, vulcanising agents, lubricants, plasticisers and other constituents of the elastomer can leach into the drug solution. These leachables can interact chemically with the API, leading to degradation, loss of bioactivity or the formation of impurities. In some cases, they may elicit immunogenic or toxic responses, resulting in serious patient safety concerns.2,6,7

“LEACHABLES OR DEGRADATION PRODUCTS CAN LEAD TO REDUCED DRUG EFFICACY OR ALTERED PHARMACOKINETICS, DIRECTLY IMPACTING THERAPEUTIC PERFORMANCE.”

Consequences for Safety and Efficacy

The implications of E&L dynamics are multifaceted, encompassing both scientific and operational challenges. Leachables or degradation products can lead to reduced drug efficacy or altered pharmacokinetics, directly impacting therapeutic performance.2 In some cases, these unwanted interactions may cause unexpected adverse reactions in patients, posing potential safety risks.2

From a compliance standpoint, regulatory non-conformance can lead to batch rejection or delayed product approval.5 Moreover, the need for additional testing, reformulation or product recalls can significantly increase costs and extend development timelines, making proactive E&L control a critical element of both quality assurance and risk management in parenteral packaging.

Given these risks, global regulatory bodies are now increasing scrutiny on E&L profiles in parenteral packaging systems.8 Advanced analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP/MS) have become standard tools for characterising material interactions and ensuring compliance.7

BARRIER FILMS AND THEIR ROLE IN REDUCING MIGRATION

How Barrier Coatings Work

To minimise direct contact between the elastomer and the drug product, manufacturers employ barrier films that act as chemically inert shields.9 One of the most established solutions is ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), used for instance in Aptar Pharma’s PremiumCoat®. This coating forms a thin, highly stable film that significantly reduces extractables and limits leachables, protecting sensitive molecules from unwanted interactions.10

Analytical Validation

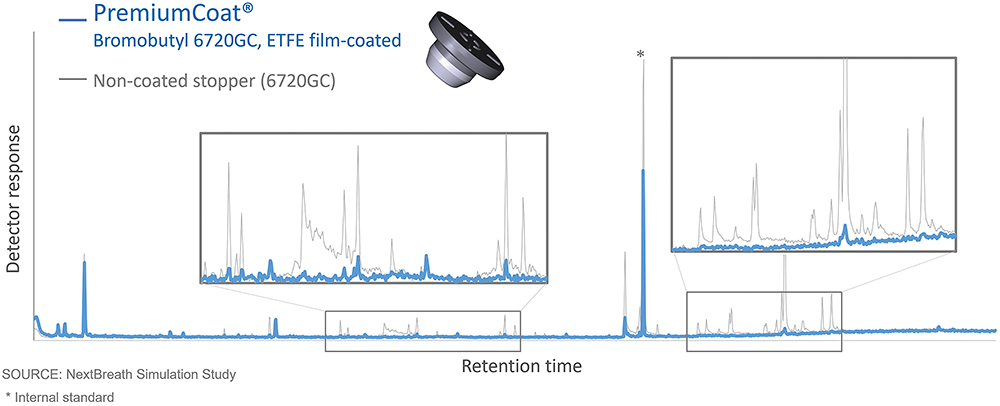

Comparative studies consistently demonstrate the benefits of ETFE-coated stoppers in reducing chemical migration. PremiumCoat®, in particular, shows lower overall extractable levels compared with an uncoated equivalent (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chromatogram from a simulation study showing probable leachables extracted using a water–ethanol solvent system after 12 months of storage at 25°C, comparing PremiumCoat® with an uncoated stopper. The results highlight the substantially reduced extractables profile of PremiumCoat®, demonstrating the coating’s effectiveness in limiting chemical migration and enhancing long-term stability compared with its uncoated version.

A Benchmark for Clean Performance

Formulated and engineered to the highest pharmaceutical standards, PremiumCoat® components share Aptar Pharma’s proven bromobutyl formulation (6720GC), a high-purity elastomer containing few ingredients to ensure consistent chemical and mechanical properties. The ETFE coating provides an additional protective barrier between the drug product and the elastomer, further minimising the risk of interaction and contamination.

“PREMIUMCOAT® IS COMPATIBLE WITH STANDARD STERILISATION MODES, MAINTAINING LONG-TERM MATERIAL STABILITY AND BARRIER PERFORMANCE.”

This combination provides excellent chemical resistance across a broad pH range and against common solvents, while ensuring consistent E&L profiles that simplify regulatory documentation and qualification. PremiumCoat® is also compatible with standard sterilisation modes, maintaining long-term material stability and barrier performance.

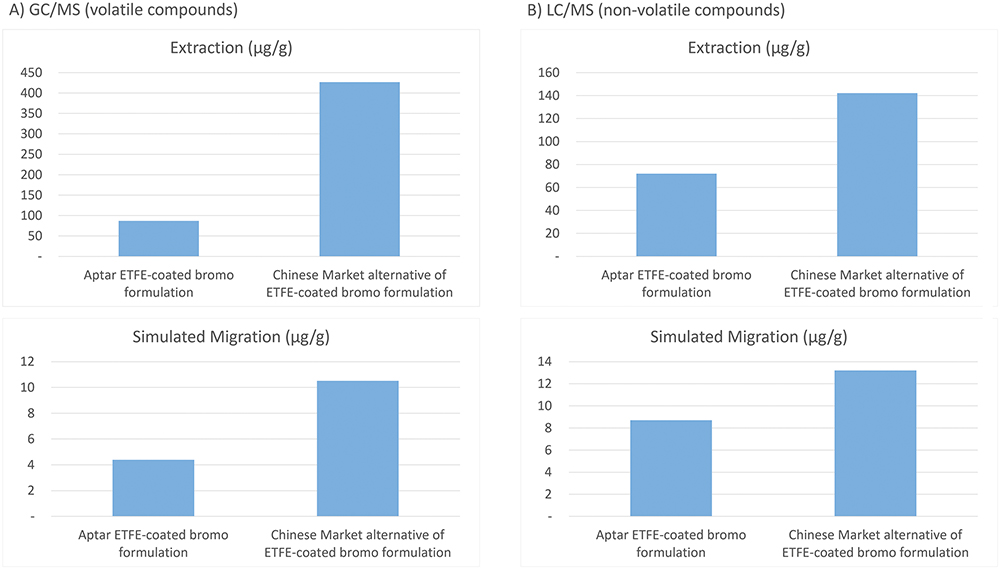

To offer deeper insight into how formulation purity and barrier performance are linked, Figure 2 compares extractables and migration results for PremiumCoat® and another ETFE-coated stopper. Extractables testing primarily reflects the composition and cleanliness of the rubber base, while migration studies demonstrate the added protection provided by the ETFE coating. These results show that PremiumCoat® is superior in limiting compound transfer, largely due to the high-purity underlying elastomer. While the ETFE film reduces migration, the inherent quality of the elastomer remains the key determinant of overall performance.

Figure 2: Analytical comparison of volatile and non-volatile E&L using GC/MS and LC/MS, including both extraction and simulated migration studies. PremiumCoat® is compared with another ETFE-coated stopper, illustrating that overall performance depends on both the barrier film and the quality of the elastomer.

Regulatory Context: PFAS Restrictions

PFAS substances have long been valued for their chemical resistance, low surface energy and durability in coating applications. These attributes made fluoropolymer chemistries, such as ETFE, an ideal choice for high-purity pharmaceutical packaging.9

In recent years, however, growing environmental and health concerns have prompted regulatory measures to limit PFAS use.3 The EU’s proposed Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) restriction and the US Environmental Protection Agency’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap are pushing the industry to lower fluorine content or introduce PFAS-free solutions.3,11 An update to the EU PFAS restriction proposal introduced a new sector – “other medical applications” – which specifically covers immediate packaging components such as fluoropolymer-coated plungers for prefilled syringes and rubber stoppers for vials. Given the low substitution potential, a 12-year derogation period following a 1.5-year transition period has been proposed for this sector. ECHA’s final opinion is expected to be submitted to the European Commission by the end of 2026.12

For pharmaceutical packaging suppliers, the question is not only about regulatory compliance but also portfolio continuity. Depending on future exemption definitions, polymeric PFAS materials may remain permissible within strict limits (e.g. individual non-polymeric PFAS <25 ppb) or may require total substitution.3

The key challenge is ensuring that any transition occurs without compromising drug compatibility, safety or supply reliability.

“THE ONGOING PFAS TRANSITION REPRESENTS BOTH A PIVOTAL CHALLENGE AND A SIGNIFICANT OPPORTUNITY FOR THE PHARMACEUTICAL PACKAGING INDUSTRY.”

The Search for Alternatives

The ongoing transition away from PFAS represents both a pivotal challenge and a significant opportunity for the pharmaceutical packaging industry. As regulations evolve, finding viable alternatives demands a careful balance between performance, purity, regulatory compliance and cost-effectiveness. Achieving this balance demands a comprehensive approach that simultaneously addresses material composition and coating strategies, ensuring future solutions can match or exceed the functionality of current fluoropolymer-based systems.

Technical Requirements for New Generations of Stoppers

Future-ready elastomer stoppers must effectively manage E&L while ensuring overall stability and performance in pharmaceutical applications.6 To achieve this, stoppers must meet functional performance expectations defined in international pharmacopoeias and ISO guidance, such as US Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <381>, Ph. Eur. 3.2.9 and ISO 8871-5, including fragmentation resistance, self-sealing capacity and penetrability under repeated needle penetration.13–15 They must also maintain chemical resistance, preserve closure integrity and feature non-stick surface properties to minimise particle generation.6,8,13

Compatibility with multiple sterilisation methods, including steam and gamma irradiation, is essential,13,14 as is biocompatibility in accordance with ISO 10993 and other applicable local requirements.15 Finally, stoppers must exhibit mechanical robustness under repeated stress to ensure dependable performance throughout their lifecycle.6,13

Achieving this balance also depends on high processability and scalability, enabling consistent manufacturing at industrial volumes without compromising quality or sustainability.

Simplifying Base Formulations

One of the most effective pathways to lower E&L risk is to simplify the elastomer composition itself. Reducing the number of additives and optimising the curing system can lead to cleaner base rubbers with fewer potential extractables.13

Different elastomer families offer distinct trade-offs that must be considered:

- Chlorobutyl provides low gas permeability and excellent chemical resistance, but has more limited processability16

- Bromobutyl offers faster curing and good heat stability, although it can present with slightly higher extractables than chlorobutyl, depending on the specific formulation17,18

- BIMS delivers outstanding gas barrier properties but comes with more complex processing requirements.19,20

“CHOOSING THE RIGHT BASE REQUIRES CAREFUL EVALUATION OF DRUG COMPATIBILITY, COATING ADHESION, STERILISATION METHODS AND ALIGNMENT WITH EMERGING PFAS-FREE STRATEGIES TO ENSURE BOTH PERFORMANCE AND COMPLIANCE.”

Choosing the right base requires careful evaluation of drug compatibility, coating adhesion, sterilisation methods and alignment with emerging PFAS-free strategies to ensure both performance and compliance.

Customer Needs and Portfolio Adaptation

For pharmaceutical companies, change management is as critical as technical performance. Customers seek continuity of supply for validated components, transparent data packages supporting comparability and regulatory filings, and predictable transition plans that minimise the need for reformulation or requalification.

Packaging suppliers such as Aptar Pharma, in turn, are adapting their portfolio to offer dual-track solutions: maintaining existing coating technologies for current markets, where compliant, while developing PFAS-free alternatives to ensure future readiness.

This approach enables pharmaceutical customers to plan transitions strategically, selecting the most appropriate materials based on regulatory timelines, drug sensitivity and risk tolerance.

Ongoing R&D Directions

With more than 50 years of experience in the development of elastomeric formulations to address existing and emerging therapeutic classes and de-risk drug development, Aptar Pharma Injectables is actively exploring fluorine-free barrier coatings that replicate the protective benefits of ETFE without relying on PFAS chemistries.

These strategies can be combined – high-purity rubber formulations with fluorine-free barrier coatings – to achieve pure, reliable elastomer solutions. Such developments aim to establish a new standard for parenteral packaging: PFAS-free, low E&L and regulatory-ready, ensuring that future elastomer systems continue to safeguard drug integrity and patient health.

CONCLUSION

The evolving regulatory landscape, particularly PFAS-related restrictions, is driving a fundamental shift in parenteral packaging design. Elastomer stoppers and plungers must now balance multiple, often competing, requirements: minimising E&L, ensuring chemical and mechanical stability, maintaining closure integrity and complying with global biocompatibility standards. Achieving this balance requires innovation in both base elastomer formulations and coating strategies, with simplified high-purity materials and advanced barrier films providing promising pathways towards future-ready solutions.

For pharmaceutical companies, these developments highlight the importance of proactive portfolio adaptation. Selecting stoppers that meet evolving regulatory and technical standards while supporting operational continuity is critical for safeguarding drug efficacy, patient safety and supply reliability. As research continues into fluorine-free coatings and optimised elastomer systems, the industry is moving towards a new benchmark for parenteral packaging.

REFERENCES

- Lv Y et al, “Pharmaceutical Packaging Materials and Medication Safety: A Mini-Review”. Safety, 2025, Vol 11(3), p 69.

- Cartledge B et al, “Predicting Extractables and Leachables from Container Stoppers”. BioPharm International, 2020, Vol 33(8), pp 40–44.

- “Annex XV Restriction Report”. European Chemicals Agency, Mar 2023.

- Scheringer M, “Innovate beyond PFAS”. Science, 2023, Vol 381(6655), p 251.

- “Guidance for Industry: Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics. US FDA, May 1999.

- Mathaes R, Streubel A, “Parenteral Container Closure Systems”. In “Challenges in Protein Product Development” (Warne N, Mahler HC, eds). AAPS Advances in the Pharmaceutical Sciences Series, Vol 38, pp 19–202.

- Sica VP et al, “The role of mass spectrometry and related techniques in the analysis of extractable and leachable chemicals”. Mass Spectrom Rev, 2020, Vol 39(1–2), pp 212–226.

- Kikovska-Stojanovska E, Agarwal S, “Chapter 30 – General analytical considerations for parenteral products”. In “Specification of Drug Substances and Products (Third Edition)”, 2025, pp 715–725.

- Kushwaha P, Madan AK, “Extractables and Leachables: An Overview of Emerging Challenges”. Pharmaceutical Technology, 2008, Vol 32(8).

- Gardiner J, “Fluoropolymers: Origin, Production, and Industrial and Commercial Applications”. Aust J Chem, 2014, Vol 68(1), pp 13–22.

- “PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021—2024”. US Environmental Protection Agency, Oct 2021.

- “Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)”. European Chemicals Agency, Jun 2024.

- Hopkins GH, “Elastomeric closures for pharmaceutical packaging”. J Pharm Sci, 1965, Vol 54(1), pp 138–143.

- Straka A, “Sterilization Effects on Elastomers in Sterile Parenteral Drug Products”. Pharmaceutical Technology, 2015, Vol 2015(2).

- “Guidance for Industry: Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, “Biological evaluation of medical devices – Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process”. US FDA, Sep 2023.

- Sreehari H et al, “Evaluation of solvent transport and cure characteristics of chlorobutyl rubber graphene oxide nanocomposites”. Mater Today Proc, 2022, Vol 49(5), pp 1431–1435.

- Gökekin Y et al, “Evaluation and characterization of different extraction methods for obtaining extractable and leachable materials from rubber stopper systems used in pharmaceutical products”. Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 2025, Vol 216, art 114844.

- Pöschl M, Sathi SG, Stoček R, “Tuning the Curing Efficiency of Conventional Accelerated Sulfur System for Tailoring the Properties of Natural Rubber/Bromobutyl Rubber Blends”. Materials (Basel), 2022, Vol 15(23), art 8466.

- Dakin JM, Whitney RA, Parent JS, “Imidazolium Bromide Derivatives of Brominated Poly(isobutylene-co-para-methylstyrene): Synthesis of Peroxide-Curable Ionomeric Elastomers”. Ind Eng Chem Res, 2014, Vol 53(45), pp 17527–17536.

- Jacob S et al, “Brominated isobutylene-co-paramethylstyrene with superior impermeability for tire innerliner applications”. Rubber Chem Technol, 2021, Vol 94(3), pp 549–574.