To Issue 182

Citation: “Interview with Liat Shochat: Developing Wearable Injectors”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 182 (Jan 2026), pp 108–111.

Visit EdgeOne Medical at Pharmapack Paris! – Stand 4C51

Q How does EdgeOne Medical’s experience with combination products allow you to bridge the gap in complexity when moving from a standard prefilled syringe (PFS) to a wearable device?

A When EdgeOne Medical was founded in 2012, our goal was to become a truly independent combination product development partner to biopharma, supporting the full product lifecycle from early feasibility studies through to commercial readiness, with all its different complexities. Emerging just as the combination product landscape was accelerating, EdgeOne played a contributing role in some of the industry’s earliest advances in subcutaneous delivery, spanning PFSs, pen injectors, autoinjectors and, ultimately, the first commercially successful on-body injectors (OBIs).

“MOST IMPORTANTLY, OUR FOUNDATIONS WERE BUILT ON THE DEEP EXPERTISE OF OUR TEAM, WHO HAD HELD LEADERSHIP ROLES IN PHARMA AND UNDERSTOOD THE ECOSYSTEM IN PRACTICAL TERMS.”

Most importantly, our foundations were built on the deep expertise of our team, who had held leadership roles in pharma and medical devices and understood the ecosystem in practical terms. We know and understand the regulatory expectations, development pitfalls, manufacturing requirements and the commercial realities that define successful combination product development programmes.

In short, EdgeOne Medical’s success comes from planning and executing a viable, de-risked path to commercialisation from an early stage. That’s where our experience makes the difference – knowing which questions to ask, how to connect the right disciplines and expertise and how to carry that same consistency from the lab to the patient.

Q As drug developers consider the shift into wearables, how should they think about selecting the right delivery platform?

A Across every platform, the same fundamental goal prevails – to reliably deliver the correct dose to the intended tissue depth, and to do so in a way that gives the patient confidence that they have received their complete dose. Achieving this is not a trivial task for PFSs or pen injectors, and delivering that same level of consistency with a wearable device is even more challenging, requiring the right mix of expertise and partnership to create a viable, de-risked path to commercialisation.

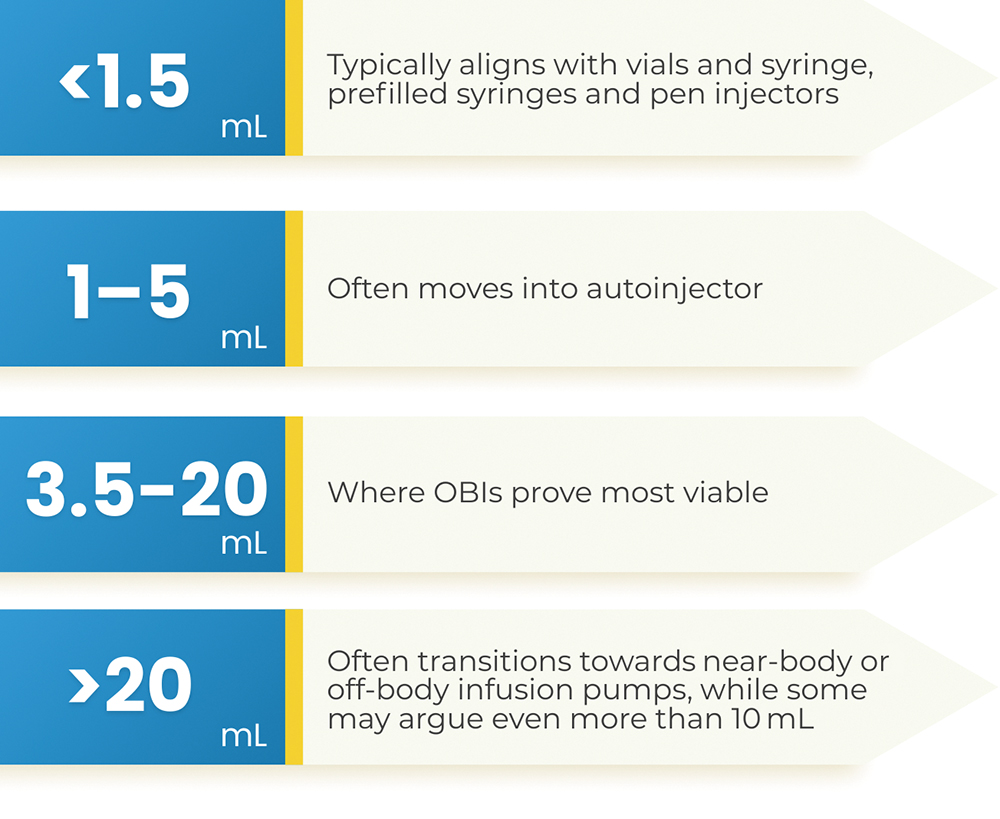

Reviewing the drug delivery device landscape, there is no single volume threshold or “magic volume number” that dictates when the therapy should shift into a wearable format. However, one can see industry trends that fall within a few practical ranges, where less than 1.5 mL is typically in a syringe or pen injector, 1–5 mL often moves into an autoinjector, 3.5–20 mL is where OBIs prove most viable and over 20 mL doses often take the form of near-body or off-body infusion pumps (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The volume ranges most suited to each injectable device format.

In addition, when choosing the right wearable platform, developers should compare and consider how the device attaches to the body, the user interface and notifications, the delivery duration and the accuracy in advance. It’s also important to check if the correct risk controls were implemented by design, such as sensors and feedback for skin-proximity detection, flow monitoring and occlusion detection, as well as factors relating to reliability, supply chain and manufacturability.

Q Drawing on your background, what are the non-negotiable technical principles that you insist on to ensure that a device is not only innovative but robust enough for commercial launch?

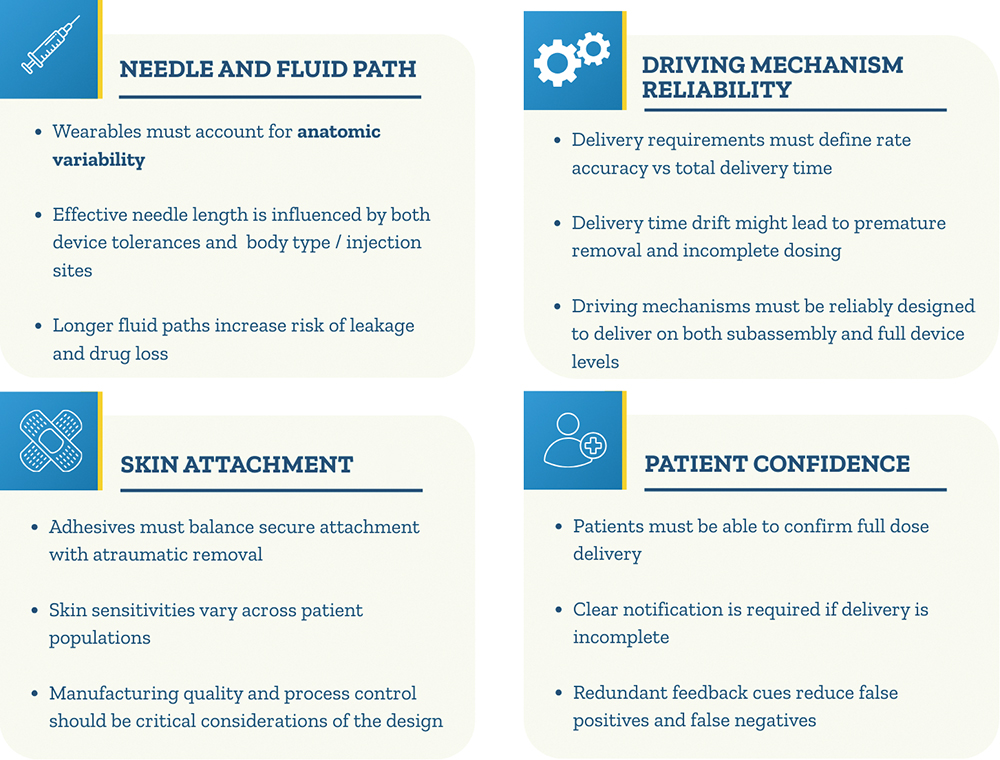

A When I consider my own work and that of my colleagues who have spent years designing wearable devices, a few non-negotiable technical principles consistently stand out. Not everyone may agree with my perspective, but it was shaped by lived experience and scars earned while bringing multiple wearables from concept to commercial launch (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Key principles for wearable device development.

“WITH HANDHELD DEVICES, THE PATIENT CONTROLS PLACEMENT AND HOW WELL THE DEVICE IS STABILISED ON THE INJECTION SITE. HOWEVER, WITH WEARABLES, THE DEVICE DESIGN MUST ACCOUNT FOR THE ANATOMIC VARIABILITY THAT INFLUENCES THE EFFECTIVE NEEDLE LENGTH AND DELIVERY PERFORMANCE.”

Firstly, needle and fluid path factors, such as needle length, dimensional tolerances and injection-site variability with different body types, are critical design considerations. Some may argue that these are the same parameters we evaluate when selecting a pen injector, which is correct. With handheld devices, the patient controls placement and how well the device is stabilised on the injection site. However, with wearables, the device design must account for the anatomic variability that influences the effective needle length and delivery performance. In addition, a longer fluid path means that the design must consider potential drug loss due to its length and the risk of leakage, especially when delivering larger volumes or operating at higher pressure.

There are also many details to consider when selecting adhesives. I tend to group them into six areas – attachment strength, ease of removal, post-use residuals, skin sensitivities, liner removal behaviour and manufacturing quality. The adhesive must attach quickly and securely, holding the device in place for the full duration of delivery. At the same time, it must be easy to remove when needed, without causing trauma to the skin or leaving residual adhesives.

In my experience, both as a patient and as someone who has evaluated many marketed devices – on more than a few devices, the adhesive can cause more trauma than the injection itself. When selecting materials, particularly for patients with sensitive skin, might be necessary to evaluate alternatives, such as silicone-based adhesives, in place of standard acrylics or non-woven constructions. Beyond the adhesive itself, the liner must peel away cleanly, without tearing or leaving fragments behind, or this may result in a user error. In some markets, including Japan, regulators and quality requirements specifically assess fibre debris generated by the adhesive, making manufacturing quality and process control considerations a critical part of the design.

Many wearable therapies have clinical requirements that require longer delivery durations, which poses the question of which is important for a given therapy – the moment-to-moment precision of the delivery rate or the overall delivery time? When answering this question, one should primarily consider usability on top of clinical considerations, such as the pharmacokinetics. For example, if the expected delivery time was stated to be five minutes, and the delivery time drifts beyond that, the user might prematurely remove the device without waiting for the completion cue, resulting in an incomplete delivery. With that in mind, it is important to define these and translate these considerations into the design requirements. Also, with the understanding that the driving force is mechanical or electromechanical in nature, it is important that the components of the drive mechanism are designed to reliably deliver effective doses and reflect it correctly in the design outputs.

“IN DRUG DELIVERY, A PATIENT’S CONFIDENCE IS MORE CRITICAL THAN THEIR COMFORT AND CONVENIENCE. PATIENTS MUST BE ABLE TO RELIABLY CONFIRM THAT THEY RECEIVED THE FULL DOSE AND, IF THEY DON’T, THAT FACT WILL BE CLEARLY COMMUNICATED.”

Lastly, in drug delivery, a patient’s confidence is more critical than their comfort and convenience. Patients must be able to reliably confirm that they received the full dose and, if they don’t, that fact will be clearly communicated. In both scenarios, clear and reliable notification methods are needed. These can be visual, audible or haptic. My recommendation is to design in redundancy, with at least two independent and aligned cues, to ensure that the patient doesn’t receive a false positive or negative.

Q From your vantage point, what were the unresolved hurdles or blind spots with wearable devices that the industry is yet to address?

A Here, let’s focus on the lenses that most directly affect wearable device development today – regulatory clarity, reimbursement and supply chain resilience. The major hurdle, and one that was a real challenge until fairly recently, is the regulatory and standards landscape. For a long time, wearable device developers had to navigate different guidance documents, including two separate US FDA guidance documents, one for infusion pumps and one for pen injectors; and two main technical standards, those being an earlier version of ISO 11608 that focused primarily on pens and ISO/IEC 60601-2-24, which was an older standard meant for infusion pumps mainly used in clinical settings. None of these reflected the needs for OBIs intended for self-administration at home. Therefore, device developers and manufacturers were operating with significant gaps in the regulatory pathway and gaps in the supporting technical standards. Today, due to good collaboration between regulatory agencies and industry, we are in a much better place.

The second challenge is reimbursement pathways. For syringes, pens and autoinjectors, these are well-established. Wearables don’t yet have the same clarity, largely because these devices are newer and less common than the others, involving more complex cost structures and device classifications. This creates uncertainty for pharma teams planning go-to-market strategies.

The third challenge, felt particularly keenly in the last several years, is supply chain resilience. We’ve seen significant disruptions both during and after the covid-19 pandemic. Ensuring consistent and reliable material availability in accordance with global regulatory requirements has become increasingly challenging. And, as some wearable systems are electromechanical, there’s additional complexity to deal with when outsourcing components – especially electrical ones. Many OBIs require batteries or an alternative energy source, causing further complexity, including safety requirements, disposal regulations and broader environmental considerations. It’s an area where I think the industry could benefit from more consistent frameworks and shared infrastructure.

Q What additional tests would you recommend wearable device developers integrate into their “planned testing”?

A On top of the essential drug delivery outputs and primary functions in different challenging preconditions, one of the first that comes to mind is from ISO 11608-6 – attachment to the body. Beyond the functional considerations mentioned earlier, development teams should evaluate initial tack, peel and shear performance, then supplement that with human-factors assessments, such as liner-removal behaviour and on-body simulations across diverse skin types and anatomical contours.

Another key area is needle and fluid path testing, including hold-up volume, leakage at vulnerable points, internal pressure build-up and tolerance stack-ups that impact effective needle penetration and dose accuracy. Because OBIs are larger and interact differently with the body than handheld devices, early drop testing is essential for confirming enclosure integrity, adhesive retention, sharp-injury protection and drive-mechanism robustness after free fall.

Third, for electromechanical OBIs, thermal-effect evaluations are needed to ensure that the heat generated by the batteries and actuators does not compromise drug stability or raise skin-contact temperatures beyond safe levels. Here, the IEC 60601 and HE75 standards are good references. In addition, if software is included, hardware, cybersecurity and software validation activities will be required. Integrating these activities early can help to identify true system vulnerabilities and prevent the late-stage redesigns that can derail wearable development programmes.

Q What is the “golden window” for engaging an organisation like EdegOne Medical?

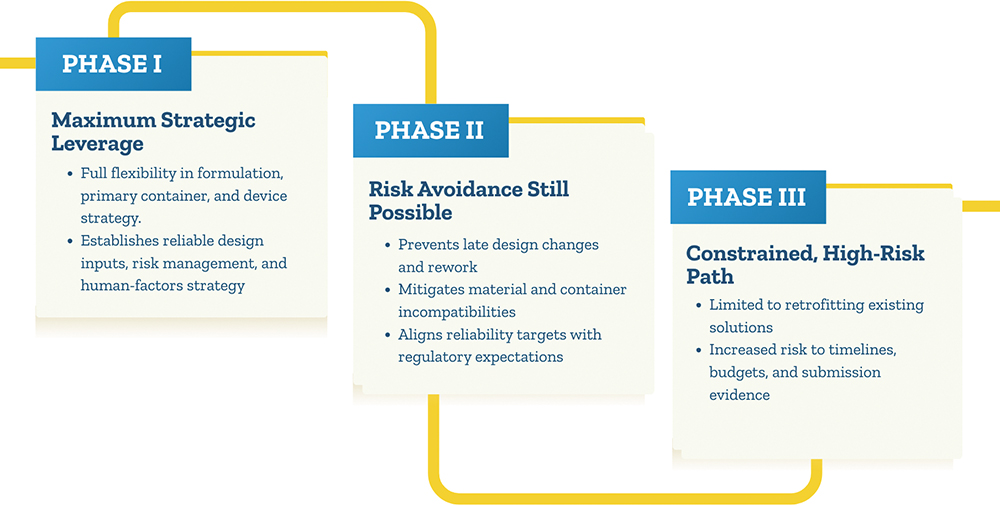

A From EdgeOne Medical’s perspective, the golden window is as early as possible – ideally through Phase I, when there is still meaningful flexibility in the formulation, primary container and device strategy. This is also consistent with broader industry and regulatory thinking (Figure 3). Engaging us early creates the greatest opportunity to shape a wearable-ready drug-device strategy by confirming technical feasibility, guiding primary container choices and then selecting the most suitable delivery platform for programme needs. In addition, it helps us to establish robust design inputs and risk management strategies, as well as to build a human factors test plan.

Figure 3: Potential stages at which a contract development organisation can be engaged.

Phase II engagement still offers significant strategic value by helping teams avoid late design changes, material or container incompatibilities and unrealistic reliability targets. By contrast, waiting until Phase III leaves limited, high-risk “retrofitting” options and constrains our ability to optimise the development programme without major timeline, budget or submission evidence impacts.

In our experience, we have had clients come to us from both sides of the spectrum – well-experienced clients engage us two to three years before their Phase II or III clinical study, ensuring good platform and component selection and sufficient time for all development activities, as well as some slack for any potential surprises or necessary changes. Other clients, who might be newer to combination product development, come to us with less than six months to go until their clinical or commercial submissions are due, which is inherently risky. In these cases, we needed to align timeline expectations and generate the required documentation and objective evidence needed to support their submission.

Q Do you have any final thoughts?

A I’ll be speaking at Pharmapack in January 2026 on two topics that are close to my heart – “Beyond the Basics: Smart Approaches to Drug Delivery System Selection” and “Piecing It Together: Overcoming Real World Challenges in Wearable Drug Delivery Systems”. I genuinely encourage our readers to reach out as this industry moves forward through open conversations and collaborations. I’m always excited to exchange ideas, compare lessons learned and support and bring to market new combination products.

Attend Liat Shochat’s talks at the Pharmapack Conference, Day 1 at 12.50 pm ND 4.00 pm.